A walk through the Musee Rodin in Paris, with a discussion of Rodin's key works and others by Camille Claudel

Auguste Rodin was one of the great sculptors of the 19th century, the first modern sculptor to merge modernity with classicism. Although his works can be found in museums and private collections across the world, the Musee Rodin in Paris is a rare glimpse into the soul of the artist, a room by room unfurling of his creative process.

The museum is at Rodin's former home, the Hotel Biron. Rodin initially rented rooms there (his housemates were Henri Matisse, Isadora Duncan, and Jean Cocteau!) and later became the sole inhabitant. In 1916, he bequeathed his estate to France for the express purpose of establishing the museum there, and the museum has been open to visitors since 1919. The collection of thousands of his sculptures, sketches and drawings, all on display in his former home at the Rodin Museum in Paris, is not by missed by any fans of his work.

The Hotel (the French term for a mansion) has retained its original rooms, each one designed to emphasize a specific theme in Rodin's oeuvre. Enter the museum first, in order to understand Rodin’s work, before strolling through the gardens to see many of his most famous works outside, as they were intended.

The museum is small enough to visit in a hour or two. Rooms are arranged chronologically and thematically, so it’s easy to follow Rodin’s career. The following guide will give you a sense of some of Rodin’s most important themes, as well as key artworks to look at, in each of the rooms.

Room I: Beginnings

The first room, filled, with works of all sizes, gives a sense of Rodin’s mastery of multiple materials.

Pierre-Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) was born in Paris, part of working class family. Largely self-taught, he completed school in 1857 and applied to the Academie of Beaux-Arts, the training site for virtually all French artists at the time. Admission requirements were notoriously lax, so to fail admission even once would stop the career of most artists. Rodin was rejected 3 times! Perhaps his works already pushed the boundaries of convention; at any rate, Rodin worked as a decorator, sculpting on his own time and submitting works to the annual Salon.

In this room, you’ll find deftly formed models in clay, wax, or plaster—Rodin’s fingers were famously facile. George Bernard Shaw, who sat for a portrait, marveled at how quickly Rodin could create his likeness.

"While he worked, he achieved a number of miracles. At the end of the first fifteen minutes, after having given a simple idea of the human form to the block of clay, he produced by the action of his thumb a bust so living that I would have taken it away with me to relieve the sculptor of any further works.”

Wood or stone sculpture is a much more arduous task. It is a subtractive process, requiring tools and physical effort to reveal a form. Rodin was equally adept at mastering these materials. The rough-hewn quality of figures that are just beginning to emerge from their stone, almost like partially formed thoughts, is something you’ll also see again.

Man with a Broken Nose, 1864 bronze

There are a few small bronzes in the room as well—this is the medium for which Rodin is most famous. Those too, originate in the small clay, wax or plaster (often a combination of those materials) models. A mold is then made from the original sculpture, either whole or in pieces. Molten metal is then poured into the molds. When it has cooled, the mold is removed and the final product is completed, with separate pieces welded together. Bronze casting was much more expensive and required another set of skills, in addition to a larger investment of materials, labor, and therefore money. But it was much more permanent, and used for large scale and public works.

The museum has multiple variations of Rodin's work. One of the reasons for such diversity is because of Rodin was able to work in different media; he could form a portrait in clay for example, then translate that same form to plaster, stone, or bronze (later, he had plenty of assitants to do it for him).

Each image is identified by its medium; for bronzes, multiple dates note the date of origin as well as the date of the casting for that specific image.

Mask of the Man with a Broken Nose was Rodin's first submission to the annual Paris Salon in 1864—it too was rejected. But the portrait (of a neighbor) shows the intense expression, surface tension, and unfinished quality that would be the hallmarks of Rodin's later works.

Rodin often used bronze casting to his advantage, by mixing and matching body parts to create entirely new works. He could also make multiple originals. One of the reasons Rodin is so well known is that he and later, his estate, allowed multiple castings of many of his works—there are 12 copies of his Thinker in museums across the world made from Rodin's original cast produced in his lifetime. After his death, Rodin left the rights of the original statue to the nation of France, and it has been reproduced.

Room II: Early Career

Sketches and paintings by Rodin

Rodin’s sense of muscular realism is clearly present in his early paintings and sketches. He captures the gravitas of his father perfectly in both the bust, one of the earliest sculptures in the museum, and the painting adjacent. The pair of male nudes visualize his thought process, from the sketch to the dynamic movement and musculature of his men.

Two portraits of the artist's father, c. 1860, Male nude studies, before 1870, Female figure, c. 1870 clay

A group of female figures modelled in clay and gracefully draped in robes show his immersion in the Beaux-Arts tradition of classicism that was popular at the time.

Room III: Emergence of a Sculptor

In this room, you'll see how Rodin diverged from tradition, creating classical heroes imbued with modern energy and movement

After visiting Italy and closely studying the work of Michelangelo, Rodin completed his first major bronze, The Age of Bronze, based on the Renaissance artist’s Dying Slave, in 1875. A lifesize male nude stretches his arms, as if awakening, to take center stage in the room.

The Age of Bronze, 1905 metal

In the idealized form and contrappasto pose, it could almost be mistaken for a classical work. And in fact, when The Age of Bronze was first exhibited, Rodin was accused of cheating--casting the nude from a live model rather than sculpting it himself (a Belgian soldier was the model). The lifelike quality is not just in the anatomical verisimilitude—it’s Rodin’s skill at using the expressive power of the body to show The Age of Bronze as an awakening modern spirit. The subtle surface tension created by the rippling muscles and dimpled bronze is a corollary to the Impressionist brushstrokes of his friends Monet and Renoir.

The statue was eventually bought by the government—but only for the cost of the materials. Rodin learned an important lesson: after that, most of his works were either smaller or larger than human scale, so that he couldn’t again be accused of cheating. Look at it closely, however, as this is one of the figures Rodin returned to when he created later male nudes.

Around the room, you’ll see all the different directions Rodin’s work would take. Fragmented and fractured forms, for the first time exhibited as finished works, represented the disjuncture of the modern world as well as the fluid nature of his own creative process.

Not always on display: A bronze St. John the Baptist shows the Biblical figure striding forward, face lost in thought. Rodin’s next major work, it too, shows him moving away from conventional sculpture. Without his traditional iconographical accessories (a cross or animal skin), John is identified only by the title. The missing arm (originally with hand upturned) gives it an air of antiquity, but the intensity of expression and agitated surface is a modern man buffeted by circumstance.

St. John the Baptist, 1878 bronze

Room IV: Artistic Circle

a series of portraits and studies of his friends, patrons, and partners

Rodin was well known as a portraitist, completing hundreds during his career. Many are unfinished, or revised in other examples, giving a sense of his process of creation as well as the distinct personalities of the subjects. Three plaster Heads of Camille Claudel show Claudel as a young 18 year old girl when she entered his student as an assistant. Eventually, she became his partner and lover. The first two look almost childlike while the third is unfinished, with seams of plaster lining her head. The melancholic expression seems to foreshadow her own future—but more on that when we arrive at the upper level.

3 plaster heads of Camille Claudel, c. 1884 plaster

Room V: The Gates of Hell

Rodin's intensity of expression is realized in the various models made for this monument.

In 1880, Rodin was commissioned to create a sculptural program for a proposed Museum of Beaux-Arts. The museum itself was never built, but Rodin spent the next three decades working out forms for a colossal entrance based on Dante’s description of Hell in the Divine Comedy. The doors were similar to Michelangelo’s Gates of Paradise at the Florence Cathedral, though Rodin conceived of his figures as springing our from the panels and door frame.

These are the characters that populated Rodin’s mind over the span of his career. In the studies of the monument and its models throughout the room, you’ll find many of Rodin’s most famous figures and motifs evolving over time. In all of them, idealized naturalism is now fully fused with the angst of the modern world. Was Rodin creating his own version of hell? Who knows--he said he always carried a copy of the text in his pocket. Perhaps his own passions and anxieties were personified in the characters. You’ll definitely see the theme of passionate love and desperation in many of his other works.

Some, like The Kiss, are more famous as stand alone sculptures, and a lifesize marble of the The Kiss takes center stage in this room. The passion of two lovers (Francesca and Paolo, condemned to Hell for their forbidden love) is reflected in their fused bodies and stippled stone. Eventually, Rodin deemed the sensuality of the work incongruous with the despair of the doors, so he removed it from his final conception. It stands alone, in hundreds of copies across the world, though, again, only the first 12 are recognized as originals.

The Kiss 1882 marble The Three Shades 1883 /1928. bronze

Surrounding the pair are different sized models of the doors, in which multiple characters (180 total) from Dante’s Circles of Hell seem to emerge from the mist. There, and in individual models around the room, you’ll find:

The Three Shades with rippling flesh and contorted poses fitting for souls condemned to Hell. Together, they point to the inscription “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.” On the door, they oversee all the other figures; in the gallery, they stand at scale, around 3 feet high. With the Shades, you can see the progression of Rodin’s style. They evolve from 19th century classical figures to increasingly distorted, expressionistic, abstract figures that reflect 20th century modernism (think Picasso).

The Thinker, originally called The Poet (Dante, who wrote The Inferno). The famous pose is actually a quote one of Michelangelo’s characters in the Sistine Chapel. But in this version, Dante sits deep in thought, anxiety across his furrowed brow and body.

The Thinker 1881/1919. bronze

A model of Ugolino and his Children (also on the lower left door) represents the 13th century count who was imprisoned for treason with his family.

Ugolino and his Children 1881 plaster

As the family died of starvation, Ugolino was left to eat his own children before dying himself. Ugolino is shown crawling across the corpses of his children, just before he begins to devour them (a life size copy is in the garden).

And the Prodigal Son, based on one of Ugolino's children. Like so many of Rodin's figures, the boy took on a life of his own, metamorphizing into the Christian symbol of redemption, imploring his father for forgiveness.

Prodigal Son, 1905 bronze

All of Rodin's most famous pieces are seen in multiple sizes and media. Compare one smaller work of the Kiss, which is much more calm, emotionally and physically detached than the larger version.

This is how the images must have evolved in his imagination over the decades of his work on this project. New styles merge with old, in this colossal survey of all the forms and emotions of the modern human experience.

The Kiss 1882 marble

While this room is a glimpse of Rodin’s passion for 3 decades, he himself never saw his vision come to fruition. The entire project 20 x 13 feet, was not cast until 1919, after Rodin’s death, and placed in the garden here (more on that later). How many of the figures can you recognize here?

The Gates of Hell 1880/1926 bronze

,Here is a resource to examine some of the smaller elements of the piece from AugusteRodin.org and RodinMuseum.org

Room VI: Public Monuments

Rodin is most known for his public monuments; here they all come to life.

In the center of the room, one man stands, hands out in supplication, enormous feet rooted to the ground. The Burghers of Calais was Rodin’s first large scale commission, to commemorate an event in the Hundred’s War against England for the city of Calais. King Edward III defeated the city, and decreed that city would be saved from destruction if the leaders (burghers) presented themselves for execution.

Jean de Fiennes 1885-86 plaster Jean d'Aire 1903 stoneware

In this room, you can see how Rodin's thoughts took form in a variety of media, as he experimented with various expressions of sorrow, anger, and resignation on each of the historical figures (lifesize figures stroll through the gardens below). Jean de Fiennes appears here in plaster, while Jean d'Aire walks in bronze.show emotions fully expressed from finger to toe.

The Burghers of Calais, modelled 1884-95; cast 1919-21

The final model shows the entire group walking together with a more restrained (and resigned) expression, symbols of self-sacrifice. The burghers complied, but when they arrived in ropes and chains, Edward spared them from death.

Rodin’s innovations can also be seen in the placement—he created the monument so that Burghers would be placed at ground level, and viewers could share their emotions and experience. This, however, was deemed too radical, and the monument was placed on a traditional pedestal instead. You’ll find a full size version of Burghers, at ground level, outside.

Burghers is the work that garnered Rodin an international reputation. When Germany occupied Paris during Worl War II, it was one of the works taken by the Nazis, though it was eventually returned.

Room VII: Fame

Rodin's creative energy is at full force

Women as muse and torment populate this room, in varied states of emotion that could also reflect Rodin’s own feelings (about women).

The Tempest 1898 marble Danaid 1885 marble Dried-Up Springs 1899 plaster

The despair of women seems to be a common theme: in The Tempest (1898), a stone scream emanates from a woman who herself emerges from the stone. That idea, of sculptures, especially females, existing in a nether world between the material and the form, is a theme that continues through his career.

Danaid (1885) began as a figure for the Gates of Hell, but eventually took on a life of her own. She is one of the 49 mythological Danaids who after killing their husbands on their wedding night, were condemned to carry water in leaking pots for eternity. The bony back of this exhausted Danaid becomes a part of the landscape, her hair flowing around her as the water flows from the jar. Her face hidden, she is a more ambivalent female figure.

In Dried-Up Springs (1889) two old women with wrinkled skin and flaccid breasts sit huddled in a cave. They are the sources that have dried up, literally and figuratively, maybe depicting his own fears about the loss of creativity? At any rate, they show Rodin delving into more exaggerated forms of emotional expressionism, similar to the work of expressionist painters like Van Gogh at roughly the same time. And recycling once again: one of the women is re-purposed from the earlier She Who Was the Helmet Maker’s Once-Beautiful Wife just adjacent.

There is a fine line between emotion and angst, desire and disgust, that Rodin skirts in many of his figures. Does he risk stereotyping women as muse or hag? That is for the viewer to decide.

Room VIII: Studio at Hotel Biron

A bronze Eve from The Gates of Hell stands, clearly ashamed of her nakedness (a rare pose for Rodin!), stands surrounded by items from Rodin’s studio. Greek pottery, the natural world (in the form of a stag), Eurasian metalwork all served as a source of inspiration for some of the works scattered about: a Madonna and child, another young girl emerging from a pot, and a fragment of a male torso.

recreation of Rodin's studio at Hotel Biron

Room IX

Upstairs is the full flowering of Rodin’s fame, beginning with Room 9, devoted to Victor Hugo and Honore Balzac.

With fame, Rodin headed a studio with a stable of assistants that translated (and combined) his smaller sculptures into any size he wanted. And he garnered the largest commissions. Hugo and Balzac were French literary giants innovators like Rodin, so he was considered a fitting sculptor for public memorials to each. This room shows how much he struggled to find the right expression and composition—but neither work received the acclaim Rodin expected.

Rodin aimed to show the passion of Hugo, who wrote Les Miserables and Notre Dame de Paris/The Hunchback of Notre Dame. By the time Rodin approached him the create a portrait, the writer had apparently tired of sitting for portraits, and only allowed Rodin a 30 minute sitting. At other points, he stood on the front porch and observed Hugo as he worked in his house—good thing Rodin was quick with his hands! Multiple heads of different sizes attempt to capture the vitality of the author, with one version exhibited at the Paris Salon.

Monument to Victor Hugo c. 1909. plasterHono

After Hugo’s death, Rodin began work on a Monument to Victor Hugo, to be placed at the Pantheon (Hugo’s burial site). Rodin experimented with different poses, settling on the writer reclining in classical robes. In one small plaster model, Rodin seems to have a tickle in his ear; the finished work was meant to have 3 female figures hovering above him, but the conception was rejected. The larger plaster model here shows Iris, representing Glory, whispering in the aged man’s ear, like Zeus on Olympus. The wind whipping the wings and robe of the figures suggests the creative energy of the author, and the angular quality of the statue is echoed by the irregular platforms of its base. The monument was never realized, but a bronze version of the plaster here was placed in the Palais Royal, and another is in the garden.

Honore Balzac: Plaster version 1898, bronze 1897, Balzac's plastered robe

With Monument to Honore Balzac, Rodin attempted to give a sense of the creative process. Balzac famously wrote in his dressing gown, and Rodin used that gown (also on display) to give dignity and cover to Balzac’s girth. There are studies of just the head, and Balzac standing nude. In the bronze on display, and the final version, Balzac’s head emerges from voluminous robes. The intensity of his thought spreads from his brow to his hair and even his robe. This too, resulted in an outcry for not being dignified enough, and though it is on public display today, for many years, the only public that Balzac saw were those that visited Rodin’s garden (where Balzac is still standing today).

Room X--Carriere

The most striking thing in this room is the hands.

Room 10, with The Cathedral (on left) 1905. stone

It seems fitting, considering the work of Rodin’s own hands through the museum, that in this room, they seem to be the instrument of divine inspiration. Scores of them, in plaster, stone and bronze, preliminaries for a massive 1908 sculpture originally titled. Rodin later renamed it La Cathedrale to link the joining of the two right hands to the architecture of Gothic cathedrals.

Room XI—the Art of Portraiture

continues with portraiture of friends and patron

Some were state commissions, like that of French politician Georges Clemenceau. Most of these are heads or busts—look among them and you will find painter Puvis de Chavannes, composer Gustav Mahler. Here you’ll find Rose Beuret, the mother of his only son and companion of (20+) years whom he married just months before she died. And maybe a portrait of Rodin himself—The Old Tree shows a small woman perched precariously on the tree-like torso of an old man.

Georges Clemenceau 1911/1925 bronze, Rose Beuret c. 1898 marble, The Old Tree plaster c. 1896

Room XII--Patronage

Shows Rodin’s own interest in collecting

Landscapes by Monet and Renoir, friends of the artist, are the highlight of this room. There are also three exceptional works by Van Gogh. In the two landscapes, you can see how the painter’s thick impasto brushstrokes echo Rodin’s sculptures. Clearly, Rodin must have seen the parallel as well. The Portrait of Pere Tanguy, another patron of Van Gogh, is particularly striking. In harmonies of blue and yellow, Tanguy sits surrounded by another source of inspiration: Japanese woodblock prints of Fuj and geisha.

Vincent Van Gogh, Pere Tanguy 1887, The Viaduct at Arles 1888, The Haymakers 1888

In the corner salon of Room XIII--Rodin’s Glory,

columns are capped with small scale figures by Rodin.

It is a striking tribute to Rodin’s role in remaking classicism for the modern world. Look for miniature versions of his Kiss, standing male nudes, female fragments, even an equestrian statue. The room also demonstrates Rodin’s genius for reproduction: the small plaster or clay forms created by him could remade in a different medium and scale by his stable of assistants.

Room XIV--Assemblage and Variation

shows Rodin repurposing again.

In his smaller works, Rodin ingeniously combined old and new in a variety of ways, a parallel to the assemblage works artists like Picasso and Duchamp were experimenting with. A series of figures emerge from ancient vases: a figure literally pours forth from a water jar, in another, the female hoists herself out of a jar, while next door another female seems to settle into one.

plaster figures emerging from ceramic vases, c. 1900, body parts from studio

Rodin also mixed and matched body parts for new figures: you can see the limbs from Age of Bronze repurposed on a small version of his Walking Man. Or re-sized subjects, as in the three different size heads of the statesman Georges Clemenceau, each one with a different thought.

Plaster versions of Georges Clemenceau

It’s almost as if you can see the inner working of Rodin’s brain as he returns to a motif or form, each time in a new context. In that context, maybe it's a little disconcerting to see the head of his assistant and mistress Camille Claudel enveloped by the massive

hand of Jean de Wissant one of his Burghers of Calais.

Assemblage: Head of Camille Claudel with Hand of Pierre de Wissant 1895 plaster

Room XIV--Enlargement and Fragmentation

Continues the play on fragmented forms and changes in scale, as ideas seem to grow and shrink in Rodin’s head.

Iris, Messenger of the Gods leaps through the center of this room—a fragmented female torso, muscular legs outspread—this is by far the most aggressively sexual of all Rodin’s muses. The fragmentation creates a spiral of female energy radiating from the splayed genitalia. Rodin designed this to be a part of the Victor Hugo monument, poised above his head, but one can see why it was eventually rejected.

Meditation is a female nude in such extreme contrappasto, she seems to be holding her own head! She too was recycled from earlier works: a figure from Three Shades from the Gates of Hell, also found in the the Monument to Victor Hugo. Rodin recycled earlier limbs and enlarged the legs, exposing the knees in the process. It seems to be the opposite of a meditative piece—but maybe something more similar to the artist’s own artistic meditations.

In the wall cabinets, you’ll find feet, hands limbs, carefully arranged according to size. Small fragments of John the Baptist are carefully placed in a bowl, almost like a reliquary. And colossal heads from other monuments observe the observers—a reminder the Rodin prided himself on his ability to render likeness without direct copying.

fragments from John the Baptist in wood bowl c. 1900

Plan to spend some time in Room XVI--Camille Claudel

An extraordinary glimpse into the mind of female artist and muse of Rodin.

Claudel, from a wealthy bourgeois family and sister of the writer Paul Claudel, started in Rodin’s studio at the age of 18 (you saw multiple portraits of her in the downstairs rooms). In this room, you see the merging of two extraordinary artistic talents. Multiple portraits of each other, and in some cases, portraits of the same figure, are the product of their 15 year relationship. Their talents are virtually indistinguishable –look in the cabinets for their dual portraits of The Laughing Man and see if you can determine a difference in skill or genius.

Which is Claudel? Which is Rodin? Read further to find out

It’s astonishing that the work of a young woman of 20 could be indistinguishable from a mature artist of 50—even more astonishing when you realize the obstacles that Claudel would have faced—only her father approved of her career and she had little opportunities for schooling. Yet she matched Rodin’s skills stroke for stroke, and as one of his assistants, was entrusted with some of the most difficult elements of Rodin's work (usually the hands and feet). The only real difference is in the scale of work (Claudel could not afford to work on the large scale of Rodin), the measure of fame, and how they were treated as artists.

The Wave 1897-1903 onyx and bronze

In The Wave, a triad of women (the Graces?) are enveloped by a wave, similar in format to Rodin’s Dried Up Spring seen earlier. But in this case, the figures almost seem to be enveloped by the wave as it starts to crash over them—they are victims of circumstance rather than decrepit old women

The Waltz 1893 bronze

Claudel’s attenuated figures have the agitated surface of Rodin, and it’s difficult to tell whether they are pulling apart, or coming together as the couple pitches forward, off-balance. There is an ambivalence of emotion that might have been present in Claudel’s own life—while she and Rodin were together, Rodin refused to leave Rose, the mother of his son. Their relationship began around 1882, and continued in some form until 1898.

As with Rodin, Claudel’s frenzied figures emerge from stone in fragmented forms. Do they seem more anxious or hysterical than his? Do they tell the story of the fractious relationship between the two? It’s hard to tell. They are certainly striking, and seem to show some of the well-documented mental breakdowns she experienced during and after her time with Rodin.

The corner couple, Vertimus and Pomona, shows a middle aged man tricking the nymph Pomona into a kiss. In other versions (including the one at the Musee d'Orsay), it is named Sakountala, after an Indian tale of a woman reunited with her long-lost husband.

Clotho is one of the 3 fates, the one who spins human life into existence. Here she is so skeletal it’s hard to tell her gender, and she seems blinded by the weight of her own tangled locks. Could this be what Claudel though of her own fate? Certainly fate is a theme in her work…

( both of these works are now on display at the Musee d'Orsay, along with others in her oeuvre)

Claudel, Vertimus and Pomona, 1905 marble

Claudel, Clootho, 1893 plaster

Especially The Mature Age/Destiny/The Path of Life/Fatality, Claudel’s tour de force. You can decide which title fits best. In the earliest study from 1894-95, the three figure composition is calm—you can see a man with exaggerated arms, pulled between two others representing old age and youth (although identified as female, they are almost male in form).

The Mature Age/Destiny/The Path of Life/Fatality, 1894-96 plaster

But in the finished work, after Claudel’s complete break with Rodin, the younger woman seems to beseech the man, creating a much more tortured triangular composition.

Claudel, The Mature Age/Destiny/The Path of Life/Fatality, 1894/1913 bronze

It is not known why a larger final piece was not cast, though there are some stories that Rodin, unhappy with the final version, might have withdrawn his support for the project. And Claudel herself apparently destroyed that final version in 1913.

Paul Claudel, her brother, said about this work "My sister Camille, imploring, humiliated on her knees, this great proud woman, and you know what is tearing at her, right now, before your eyes, it's her soul"

As a woman in a man’s world, Claudel had little power but through her art; tragically, the anxiety present in Claudel’s work seems to foreshadow the devastating end to her career. In 1913, just eight days after the death of their father, Paul institutionalized his older sister, against the advice of Camille’s doctors and friends. She remained confined, never sculpting again—for the next 30 years. Visited by her brother only 7 times.

It is unknown what Rodin thought of the situation. But there is some justice in that Claudel’s work stood proudly side by side with Rodin’s in the museum for decades. Since, 2017, however, she has finally achieved a museum of her own, in her hometown of Nogent-sur-Seine outside Paris. Her work is often on display side by side with Rodin, at the Musee d'Orsay in Paris, The Metropolitan Museum in New York, and the Palace of Fine arts in San Francisco.

Room XVII--Rodin & Antiquity,

you’ll find Rodin’s collection of ancient body parts, collected from Greece and Rome, here arranged like a curiosity cabinet.

The Walking Man, made from the recycled limbs of St. John the Baptist and the faceless torso of the Prodigal Son, guides you through this room. Critics disliked this work, especially the fact that it was faceless. Rodin, however, argues that it was a complete work, reinforcing the fragmentation as a symbol of the modern era

Walking Man 1907/1913 bronze

Room XVIII—Towards the 20th Century

is a final reminder that the female form was Rodin’s eternal muse.

One of the first modern dancers, Isadora Duncan, once lived in this house, too. Dance, as a physical expression of emotion, was a perfect subject for him, and Rodin reportedly preferred his models to walk (and perhaps dance) across the room as he sketched and sculpted their poses.

For Dance Movements, Rodin sculpted Alda Moreno, an acrobat, in 2 different poses. Rodin took these clay figures and split them apart casting the limbs separately. Clay versions could then be molded, then mixed, matched, and modified in different ways—14 versions in all. The figures somersault, skip, bow, and otherwise dance across the room. This series was completed in 1911, 4 years after Picasso’s first Cubist work. One wonders if this was Rodin’s own version of a Cubist technique? Or just a modernist assembly line production?

Dance Movements 1903-1912 clay

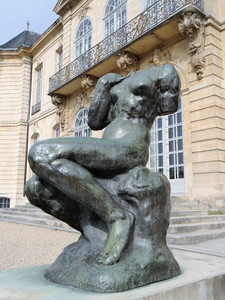

Rodin Garden

As you explore the gardens outside, you’ll be accompanied by a cast of Rodin’s characters—all lifesize, in bronze, as they were intended.

Starting at the entrance, you'll find the Burghers of Calais on the streets of Paris—now at street level, as Rodin intended.

The Burghers of Calais, 1889-1926 bronze

The Gates of Hell in all their terrible glory, just as Hugo conceived them, with Adam and Eve serving as guardians on either side. Looking at them here, you’ll get a sense of Rodin’s genius in the size (almost 20 by 13 feet) and variety of the monument, as all the models from the museum come to life. The Three Shades oversee the garden, with The Thinker brooding directly below.

The Thinker on the Gates of Hell, The Three Shades 1886

And walking through the garden, recognize the other characters that inhabited Rodin's mind and studio...

Victor Hugo with Glory still tickling his ear is the marble collection. Balzac is still in his dressing robe...all the individual burghers of Calais, now freed from their chains... and in the fountain, Ugolino, escaped from the Gates of Hell, is still crawling over his children.

Monuments to Victor Hugo and Honore Balzac 1900 & 1892-97; Jean de Wissant, Ugolino

Returning to the front, you can travel back in time towards Rodin’s early classical works, like the ancient earth goddess Cybele, eternally headless, and a Fallen Caryatid, crushed under her burden of stone.

Cybele, 1908 bronze Fallen Caryatid 1883/1910 bronze

Last stop is The Thinker, still musing in a topiary terrace. A fitting end, considering this is the work one thinks of with Rodin. Hopefully the museum shows you all the other figures formed from the fingers of Rodin.

If you're thinking about where you might see more of Rodin, be sure to visit the Musee d'Orsay, which has an excellent collection of Rodin and Claudel's work.

If you're hungry or thirsty, or just want to enjoy the beautiful setting (popular for weddings), Tribute to Claude Lorrain beckons you to the café, which has drinks, desserts and snacks to enjoy in the garden.

https://www.musee-rodin.fr/

Tribute to Claude Lorrain 1889 bronze

Comentarios