For California Maidu artist Harry Fonseca (1946-2006), the world began with Helin Maideh (Great Person), who first created water and air. He floated on a raft with Turtle at the beginning in that formless world with no sun, no moon, no stars. He was lonely, so he thought into creation Kodoyampeh (World Maker), and together, the three set out to make the world. Turtle dove into the water over and over for days on end—until finally he returned with a tiny bit of earth from the bottom of the waters.

They took the dirt, formed it into a cake, anchored it with four white feathered ropes, and that became the world, with its hills and mountains, lakes and streams. Helin Maideh next made the animals, fishes, birds and plants. Then the three set out to populate the earth. There are many stories and many versions, but in one, Kodoyampeh put a willow stick under each arm, and went to sleep. When he woke, the first man and woman were there to greet him.

Kodoyampeh made the world comfortable for First People, with food and fire, and changing seasons: Rain Season (kummini), Leaf Season (yominni), Dry Season (ilaknom), and Falling Leaf Season (matminni). He gave them songs and stories to tell to their children and grandchildren.

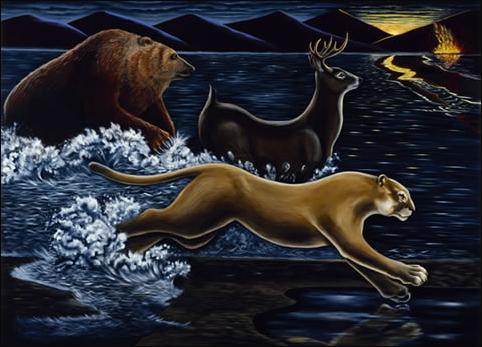

Every Maidu group, every California group, had a different story to tell. Why? The landscape changes in each place as the Ancients travelled through the world. In some spots, snow was piled to make mountains; in others, creatures rested and were turned to stone. The Miwok of Yosemite tell the story of Little Bear, who fell asleep and awoke to find his rock had grown into El Capitan! Welgatim’s Song (at the Crocker) tells the story of Coyote, so mean to his wife Welgatim (Frog-Woman), that she causes a great Flood to wash all the troubles of the world away. The Race for Fire (at the Maidu Museum) tells about the animals who raced to bring fire back to the world after the Flood. Who do you think won?

Judith Lowry (Pit River/Maidu) grew up nearby (in Susanville) listening to the Maidu stories of her father and family. She loved all stories, and grew up to paint them herself. In her stories, the animals come to life (sometimes Coyote), sometimes others, to teach children the important lessons of life. Be good to your family. Do your best for others. Don’t be too greedy!

Harry Fonseca (1946-2006), of Hawaiian, Portuguese, and Nisenan Maidu descent, was born and raised in Sacramento. As a student at Sac State, he took classes from Wintu artist Frank La Pena and worked with Maidu elders like Frank Day, Henry Azbill, his uncle. Together, they founded the Maidu Dancers and Traditionalists, which recaptured the many native ceremonies that had been lost throughout the Sacramento region: Maidu, Wintun, Miwok, Pomo, and others. Ceremonies, with their songs, dances, stories and most important, gathering of people, are always an important means of passing on cultural beliefs to the next generation.

As an artist, Fonseca told stories in many ways, and often used Coyote as a character in many of his paintings. In California tales, Coyote is a giver of good things, but also naughty. He is trickster, just like his cousins Raven and Rabbit, Iktomi and Anansi. He steals the sun for the people and brings them fire. He knows how to have fun, riding stars and tricking other creatures. But he is often greedy: stealing food, chasing girls, thinking he is the best. In short, he is our best and worst impulses, always trying to create a better world, but his ego usually gets him in trouble along the way. He teaches us what to do—and what not to do—in a way that makes everyone laugh.

Fonseca used his paintings of Coyote to show that California natives are alive and well, thriving in the modern world. He is usually painted in a cartoon-like style, with thick lines and bright colors, because at his core, Coyote is a comic (and often people learn best through humor).

As a Deer Dancer, Coyote wears a magnificent feather skirt and red flicker (woodpecker) headdress. He walks with two sticks to mimic the walk of a deer—but he also wears his tank top, jeans and hightops. In today’s world, Coyote doesn’t have to choose between traditional and modern.

He wears Hawaiian shirts and leis, leather jackets and boots; he surfs, skates, and bikes. He wears a feather headdress like a Plains warrior. With his girlfriend Rose, he sings in an opera, or dances the jitterbug. Look closely and you can always see his ears and tail—that’s how you know it’s Coyote.

Harry Fonseca was interested in all the Maidu stories—and all other stories, too. He travelled to ancient sites across the continent to the petroglyphs, stories left in stone by past peoples on cliffs and boulders from the Southwest to the Canadian border, and all across the world. He looked at the petroglyphs inscribed into the rocks in the park right here in Roseville.

Instead of stone, he inscribed his stories on canvas, using the gold of the California foothills and blues of the Delta waters as a backdrop for his Creation Story. Look closely and you can see Great Person and World-maker as Big Heads with their feathered headdresses and magic hands, coming down on feathered ropes, putting the world into place as the Ancients look on.

The sun and stars are in the corner; below, the first people are there at home, with first fire, a gift from the Ancients. You can see their footsteps as they passed through this new world. Rivers, streams and lakes lace the land. Deer leap through a landscape punctuated with trees-the pines and oaks common to all of California. In some stories, leaves tossed in the air become the first birds. In other stories, Coyote is present when the world is made-- Can you find Coyote’s footsteps?

Circles and spirals mark special spaces—home, or the roundhouse where ceremonies were held. And sacred circles frame the story—because like a story, a circle has no beginning or end.

Fonseca’s Creation Story is that of his people. Like any story, it changed with each telling. His painting, however, is on permanent display at the National Museum of the American Indian—it symbolizes the creation story of the spirits, ancestors, and all indigenous people.

Special thank you to Diana Almendariz, Strawberry Valley Maidu!

PROJECT: Make your own petroglyph, or story in stone

Materials: paper, black crayon, blue and yellow pastels, cardboard cutouts of petroglyphs

Prep: trace common petroglyph designs for each table group to use as model or trace

Process:

What is your creation story? Think about the characters and place of your own story and write a paragraph to tell your creation story.

Who are the people in your life you’d like to show?

Where are the places you like to be or go?

What are the details of landscape of animals you’d like to add?

You can add rivers, lakes, streams or hills and mountains

Trees, flowers, grasses

Animals: deer, bear, rabbits or snakes, birds, dogs or horses

Create petroglyphs: using a black crayon, “carve” your own petroglyphs

Create background: using blue, yellow and gold pastels, rub backgrounds. You can also rub over carpet or concrete sidewalk to get a textured effect.

Add border to frame your picture. Try small spirals or circles like Fonseca

References and Resources:

Azbill, Henry and Craig Bates, The Maidu Story of Creation, NCC p. 38

Bibby, Brian: 500 Nations, Cross of Thorns,La Pena; Dream Songs and Ceremony